Many among aspiring, present, or retired law enforcement officers can say they had one or more beat cops or TV characters role-modeling heroic police work when growing up as a kid. I was enamored by NYPD cops while growing up in New York City, thus I, for one, can attest to this.

My police career was intentionally predicated on lacing up my duty boots to then place myself in others’ shoes, trying to glean their perspective from where they stood…doing what they were doing—a study, of sorts. Course correction is a staple ingredient among the solutions cops implore and deliver.

In that context, exemplifications of cops serving as beacons for so many abound (even though mainstream media waxes with anti-police propaganda to greedily aggregate gross profits on the backs of unquestioning viewers tapping salacious titles subordinating heroic public servants).

Much like the Norman Rockwell iconic painting depicting a runaway boy sidling a state trooper at a diner, cops consistently reflect that same image by meeting many in the middle, pre-emption and mitigation at the core of concentrated efforts.

Canton, Ohio police Officer LaMar Sharpe and his Be a Better Me Foundation is a great example of what a cop can do for/in his jurisdiction in terms of both community policing and mentoring youngsters to do the right thing, to be the best person they can be.

(Photo courtesy of Officer LaMar Sharpe’s “Be a Better Me Foundation.”)

It’s no wonder Officer Sharpe caught the eye of civic organizations and Mike Rowe’s “Returning the Favor” show, highlighting what a cop mentoring kids looks like:

In an increasingly chaotic, complex, and confusing world, we certainly owe it to youngsters to offer examples of measured responses resulting in positive gains. It’s Role-modeling 101.

Sometimes, the flipside of an otherwise adversarial encounter involving cops and wayward citizens circles back years later, whereby parties reconvene and share godsends and success stories over handshakes and hugs.

From Officer Darren Derby we have the following recent example:

“In early 2020, I was working a hospital detail watching a prisoner. Even while loaded up on Haldol, the patient had enough strength to throw around nurses and doctors, all while being strapped down. Me and another officer had to jump on the bed to hold him down. The patient was extremely intoxicated. The worst I have seen in my 21-year career.

“I stayed in touch with him after he got out. It has been a little bit since I’ve run into him, but something brought us together this morning. Thomas couldn’t wait to tell me that today marks 500 DAYS SOBER! After seeing him in the hospital that night, I thought for sure we would likely find him dead somewhere from drinking.

“Thomas is living life and has a glow about him that he himself hadn’t seen for several years because of alcohol addiction. He has his own apartment and is looking to bring his dream of being a tattoo artist come true. He told me people wanting to get sober often ask him what the magic was to get sober, advising, ‘There is no magic, you just have to want it.’ Thomas, I know your mom must be so proud of you!

“If you are struggling with addiction, I hope Thomas’s story can help you realize that you can do it too. Let those who want to help you, help you!” The last few words from the mouth of a cop positioned accordingly and extending a guiding hand.

(Photo courtesy of Officer Darren Derby.)

Looking at Officer Derby’s page, you can see he is a master at mentorship.

Despite the many episodes just like these, anti-police nonsense still pervades.

With the glut of ultracrepidarians oozing from the baseless-opinions boxes, it makes absolute sense to not only consider experts who can not only relate sound advice in the field of law and order, criminal justice, and constitutional provisions, but to also tailor upstanding principles toward living a law-abiding life in favorable constructs—aka doing the right thing.

Contrarians unsettled by the preceding paragraph are part and parcel responsible for ill-conceived behaviors seemingly rampant in present-day society—courageous cops are at the opposite end of that spectrum.

Despite polls showing most Americans support law enforcement, these havens of hateful, lying squawkers typify exactly what we may likely continue to experience, to the dismay of many. Succinctly stated, “Americans’ trust in the Black Lives Matter movement has fallen and their faith in local law enforcement has risen since protests demanding social justice swept the nation last year,” the exclusive USA TODAY/Ipsos Poll indicated.

We’ve all entered this world with a clean slate; it is programming which shapes our thinking and thus behavior and good or bad choices in life.

A study conducted by Prescott Lecky was based on the neuroscience we know as psycho-cybernetics, examining the neural pathways of the human brain and how negative programming translates to how we live and act. As described by Dr. Maxwell Maltz, a noted practitioner of properly programming the brain for success, Lecky “brought about almost miraculous improvements in the grades of school children by showing them how to change their self-image… Lecky concluded that poor grades in school are in almost every case due in some degree to students’ self-conception and self-definition.”

(Photo courtesy of the Basketball Cop Foundation.)

Unequivocally, youngsters need proper guidance.

That makes an excellent case for the imperative roles cops play as school resource officers in school settings across the nation (one facet among many cops implement). SROs serve as mentors ideally positioned where learning is the objective, and the student base is prevalently convened for concentrated efforts. School districts and boards seeking to downsize or outrightly displace SROs are undoubtedly shortchanging kids’ potentials.

It is Dr. Gabor Maté’s cornerstone belief that every piece of brokenness having the potential to materialize in bad behavior stems from one or more unmitigated childhood traumas. Noted clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson has troves of material bolstering the premise that early onset traumas can malign a person’s life course (troubled teens) while also underscoring that brokenness can be undone. Dr. Peterson also mentions police officers being at the fore of mitigating matters on behalf of people trying to assuage varied dilemmas.

As well, some of Dr. Maté’s many lectures on the subject specifically mention public safety professionals bearing witness to the so-called broken souls requiring overdue attention. And that punctuates our topic today: cops are pivotally positioned to meet, assess, and serve as mentors in varied ways based on input they either receive verbally and/or observe physically. It’s a staple in every call to which law enforcement officers respond. Address the dilemma and redress it with resolution, serving as a guiding beacon for those who may have lost their compass/direction.

Although I only recently started to study Dr. Maté’s material, I have many memories of innumerable people I encountered as a cop, each with one or more relatively discernible traits indicative of some bad scene in the past. As each duty day gives way to one after another, cops become quite adept at “reading people,” and that correlates to any police officer’s bevy of resources to effect positive change.

Conversely, since cops are responsible with public service modalities, a humongous one with which they embrace for the good of all (themselves included) is simply being present whether summoned or scheduled or via organic chance meeting.

I’m dating myself here, but I liken it to when I were a boy scout under the tutelage of scoutmasters teaching skills with applications throughout life. That experience coupled with numerous interactions with NYPD beat cops manifested in a destiny I kept crystal clear, achieving the rite of passage even after a long/recurring bout with cancer afflictions.

I didn’t have school resource officers (SRO) when I was a student in NYC, but I do know the value they have and the investments they make in thousands of kids walking the campus grounds or traversing the hallways while transitioning from class to class.

Social media platforms are laden with positive interactions, many containing testimonies from students detailing salvations of all sorts, thanks to SROs who were there for them and took the time to listen and/or provide mentorship.

Shadowing some of my cohorts who served as SROs in our city schools, I was captivated by plenty of youngsters who gravitate to the uniform, ask questions, exude wonderment, several of whom swiftly form rapport enough to share abuse/neglect at home or destitution or internal strife they felt no one else would understand. That is huge!

The fact that an adolescent approaches a police official and candidly opens up surely makes a cop’s day, career even. How many are LEOs salvaging from the brink, by just being present and offering listening ears and safe harbor?

Just ponder how many young minds harvest deeply embedded memories of police officers who made a difference in their formative years. I’m not only referring to school-based era but also tragic circumstances in which one finds themselves as victims in a horrid real-life scenario.

For example, we recently saw an entire division of Louisville, Kentucky cops meld together and employ all the requisite police skills, tactics and strategies enabling a hugely successful save of a six-year-old child who was kidnapped by a depraved man.

It is still circulating nationally, perhaps internationally, portraying the stand-out moment when a few cops capture the perpetrator and one policeman bravely opens a car door, the windows of which are way too tinted for him to see what is on the inside, ultimately revealing a terrified child crying.

He offers consoling words, the little girl ostensibly recognizes the saving grace of a cop’s uniform, and then cries out, “I want my daddy!”

That gut-wrenching stark scenario segueing to breathtaking lifesaving involving cops, the very same public servants those ultracrepidarians speak against and wish were erased…says much about the value of public safety officials and their proper place in our society.

Whether via planned events or organic interactions, law enforcement officers are surrogates in so many ways, mentoring, guiding, influencing, encouraging, enlightening, supporting, enriching, saving…employing senses to see, hear, and speak about direction and purpose in lives seeking consolation and/or construction.

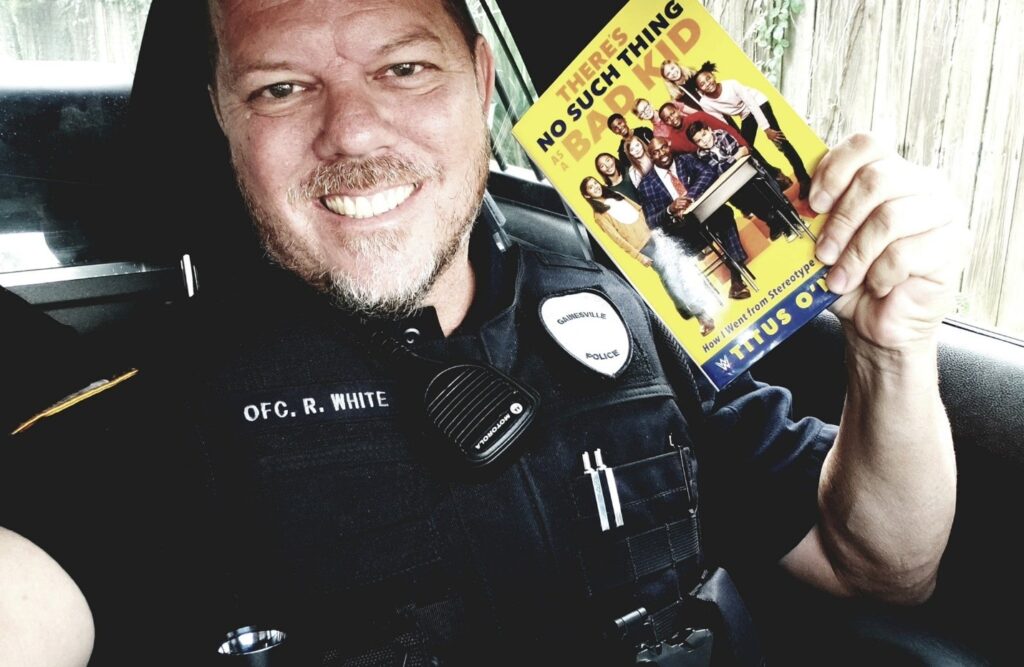

Speaking of unplanned, purely organic mentorship, check out this nugget:

Some among our society seek to denigrate and downsize the already small number of America’s police officers attending a robust population of roughly 334 million. Despite the lopsided ratio of cops/citizens, our LEOs nevertheless keep churning out stories of humanity by seeing needs and meeting those needs.

One example among many with the same premise is the Tampa Police Department’s “Teen F.O.R.C.E.” whereby Tampa cops mentor/monitor success of youngsters who “may have lived a troubled past, but” are anchored by police officers “committed to helping them focus on a bright future.”

Teen F.O.R.C.E. (Fostering Opportunity, Relationships, Community and Excellence) is a summer mentorship program offered by TPD, a cop-commodity similar to the profession-centric national model known as police explorers.

Mentorship is even a policy parcel in police agencies. Now-retired Police Chief Scott Nadeau initiated a Big Brother, Big Sister program involving his police force when he led the Columbia Heights PD.

(Photo courtesy of Big Brothers, Big Sisters.)

According to the Big Brothers, Big Sisters page, “Police Chief Scott grew up with two quality mentors — his parents. His father taught Scott and his friends to fish and hunt, and his mom encouraged them to empathize with others. The lessons had lasting effects on Scott, but modeling mentorship may have been the biggest.

“As he went through college and started his career as a beat cop, he sought out mentors for himself and eventually decided to become one. He became a Big Brother to Little Brother Marcus and saw firsthand the impact that an officer could have by mentoring a youth. After being named police chief, he made mentoring a priority for his department and saw award-winning results.”

By pure happenstance while browsing cover photos to illustrate our material today, I came upon a picture posing many of the police officer/mentors we mentioned herein, in a perfect image underscoring our story. I believe we’ve come full circle…

(Photo courtesy of the Basketball Cop Foundation)

Police mentorship is a gem with infinite value which transcends generations and potentially influences future cops to help settle our society’s woes or simply sit in constructive fashion while blending beautiful brainpower together, like the neuroscience referenced above spells out.

Let’s continue to build upon all this great humanity!