By Steve Pomper

Rosebud Sioux Tribe Police Highway Patrol SUV

This brief look at the unique operations and relationships between tribal and local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies in those areas where they converge puts lesser-known aspects of American policing on cop supporters’ radar. There are distinctive issues facing Indian nations that can severely affect law enforcement in those areas for Indians and non-Indians.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that in the U.S., there are 258 tribal police departments with at least one sworn officer. For example, the Havasupi Reservation in the Grand Canyon in Arizona has a population of only 600 people where the BIA provides law enforcement. At the other end of the scale, according to CJME AM 980, the Navajo Nation, an area the size of Connecticut, has a total population of over 300,000, with 173,000 living on the Reservation. The Navajo Nation has the largest tribal police department in the U.S. with over 200 sworn police officers.

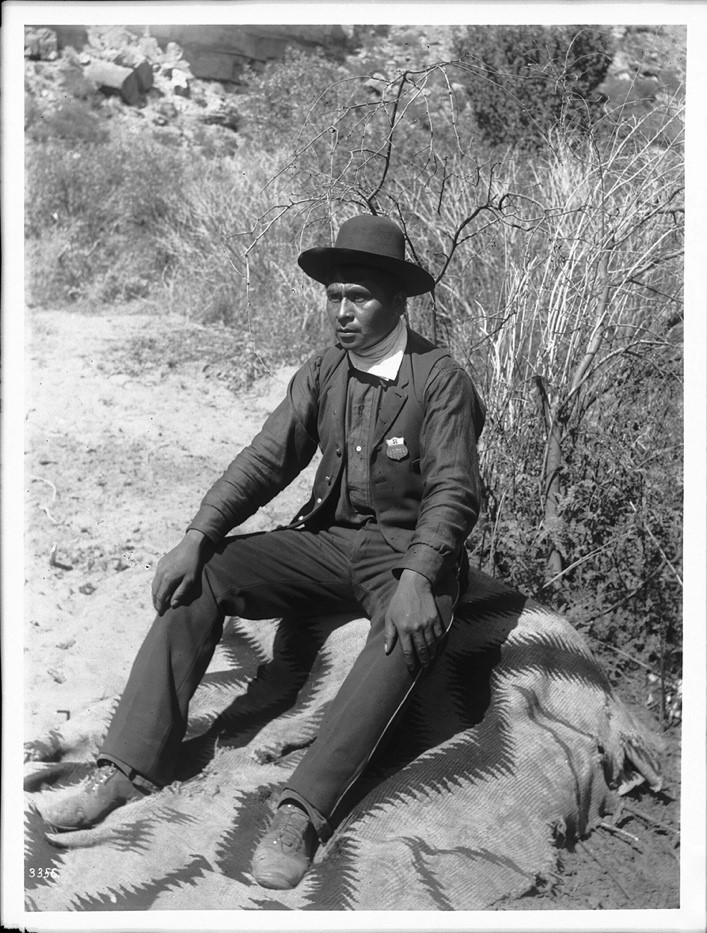

Havasupai Indian policeman, Lanoman, sitting on a blanket, ca.1900

Most tribal police officers get the same training as their non-Indian counterparts. Some go to state operated police academies, others, like the Navajo Nation Police Department, run their own training based on similar standards to other agencies.

Back in 1992, when I attended the Washington State police academy, we didn’t have any tribal cops in our class, but I saw tribal police cars parked in the academy lot, belonging to some officers attending other classes from tribal agencies across the state.

“There are only 2,380 Bureau of Indian Affairs and tribal uniformed officers available to serve an estimated 1.4 million Indians covering over 56 million acres of tribal lands in the lower 48 states.”

Some officers are tribal members while others are not, but all serve their communities with equal dedication. A smaller number of departments are under the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs), and tribes operate the rest.

Federally recognized tribes have entered into agreements with the federal government and some tribes with various state governments, like with the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This gave Indian tribes more autonomy, including in tribal law enforcement operations.

Other notable statistics show:

- Tribally operated agencies employed 3,462 full-time personnel, including 2,303 sworn (67%) and 1,159 nonsworn (33%).

- A majority of tribally operated agencies provided court security (56%) and search and rescue operations (53%).

- Thirty-seven percent of tribally operated agencies had at least one full-time sworn school resource officer.

As alluded to previously, there are also Tribal Law Enforcement Agreements with some state governments. Washington State, where I live, has such an agreement called the 2012 Centennial Accord Plan. Aside from other issues, this addresses mutual aid between tribal police, local police and sheriffs, and the Washington State Patrol.

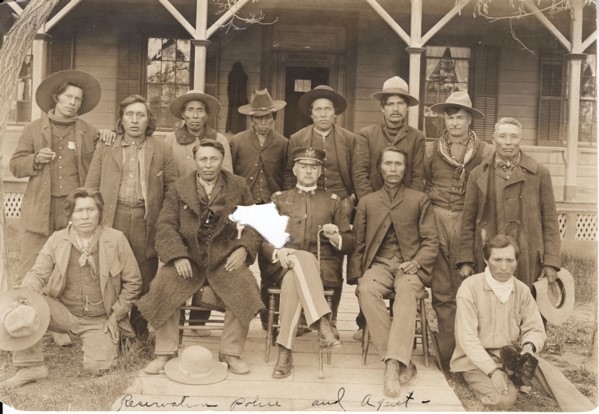

Shawnee Tribal Police captain and officer, Oklahoma

Some of these agreements are unique due to various federal treaty rights that blur state borders. For example, the above Washington State agreement includes some tribes in the neighboring states of Oregon and Idaho.

There are also some tribal police agencies that incorporate unusual cultural twists into their operations. For example, the Pleasant Point Tribal Police of the Passamaquoddy Indian Township Reservation in Maine.

They still practice the archaic custom of “Banishment” to enhance public safety in their community. This custom allows the tribal council to banish non-member residents from the reservation. Reasons include for domestic violence, which is specifically mentioned. Since they don’t banish their own violent member miscreants, booting non-member miscreants back into non-Indian communities seems only fair.

Some tribal police, like the Mille Lacs department in Minnesota, have close relationships with local non-tribal law enforcement. For example, the tribal agency has jurisdiction not only on the Reservation but also on “off-reservation trust lands” and has “concurrent jurisdiction with the Mille Lacs and Pine County Sheriffs under state law.”

There is one significant area where there has been some contention between tribal and local law enforcement. According to a 2021story from NPR, parties have attempted to gain legal clarification of tribal police law enforcement when handling non-Indians on reservations. Morning Edition’s Savannah Maher wrote, “Supreme Court Rules Tribal Police Can Detain Non-Natives, But Problems Remain.”

Tribal Reservation Police near Fort Spokane (Est. 1900)

The problems include that even though a driver may commit a traffic violation while driving through a reservation, their jurisdiction is still limited. New Mexico tribal police officer Jerome Lucero had probable cause to arrest of a driver he initially detained for a traffic violation. But, he said, “when I pull someone over, I have to take into consideration whether they’re Native or non-Native.”

Oddly, despite America’s constitutional commitment to equal justice, the quasi-sovereignty of Indian reservations continues to create a jurisdictional mess absent agreements as listed above in some states. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has partially clarified tribal police authority over non-Indians on Indian land.

Maher reported, “In United States v. Cooley, the U.S. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld tribal officers’ authority to at least investigate and detain non-Native people they suspect of committing crimes on reservations while waiting for backup from non-tribal law enforcement.”

But not to arrest them.

Officer Lucero experienced this after pulling a driver over for a traffic infraction when he quickly determined the driver appeared impaired by drugs or alcohol. Then, the officer observed what appeared to be heroin and syringes within the car in plain sight and within reach of the driver, amounting to probable cause to make an arrest. But the suspect was non-Native American.

Lucero attempted to get the sheriff’s office to respond, but they said they had no deputies available. To further muddle things, “The New Mexico State Police first told Lucero that they couldn’t spare an officer, and later said they believed state police also lacked jurisdiction to arrest the man on tribal land.” Carried to its illogical conclusion, this handcuffs the cops, not the bad guys

Due to the legal fog, Officer Lucero could only impound the man’s car and drop him off at a town off the reservation. Though the suspect had been a danger to reservation drivers and the officer caught him with illegal drugs and paraphernalia, he had to let the suspect go.

But it’s the Supreme Court that got itself (and parts of the country) into this mess. For some strange reason, “in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the court stripped tribal nations of criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives.” In explaining the opinion, the majority admitted there would likely be negative repercussions but essentially determined the consequences were none of their business. What?

Napaskiak Tribal Police Department, Alaska, with then U.S. AG Bill Barr

At least, in this more recent unanimous ruling, SCOTUS made the negative consequences partly their business. Some proponents of tribal jurisdiction over any lawbreaker on Indian land think the Court is headed in the right direction and will soon overturn the terrible Oliphant decision. Others noted that Congress also has the authority to make these changes by federal law.

However, proponents also see bigotry preventing necessary changes. They say some political leaders’ rejection of “increased jurisdiction” on Indian lands are elitist and biased against Native American law enforcement.

Officer Lucero (who is also the tribal governor) said, “We don’t have jurisdiction [over non-Natives] here on our reservation, but when us Native Americans get off the reservation, they have full jurisdiction over us.” Admittedly, this does seem to be saying non-Natives can’t get justice in Indian country. This is one of the elitist arguments the British used against colonial America before the Revolution.

Tragically, one sad occasion that links all law enforcement agencies, tribal and non-tribal, is the line-of-duty deaths of officers. As reported by Police Magazine in 2021, White Mountain Apache Police Officer David Kellywood was shot and killed in the line of duty.

The 26-year-old husband and father of two had responded to a “shots fired” call near a casino. On arrival, the suspect ambushed the officer, fatally shooting him. Another officer shot and killed the suspect after he arrived on the scene.

Thousands of people, including droves of cops from other tribal and non-tribal agencies across Arizona, the region, and the country, came to say goodbye to this dedicated public servant.

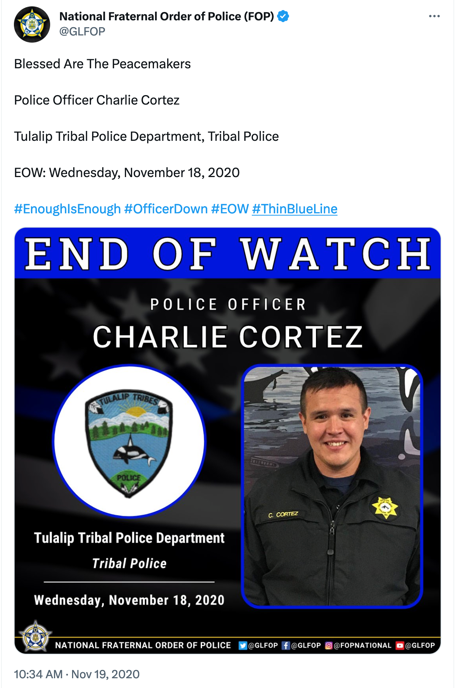

There are several Indian Reservations and federally recognized and non-recognized tribes in my area of Washington State. The nearest is the Tulalip Indian Reservation, about 20 miles north, where the Tulalip Tribal Police patrol.

Sadly, this agency also lost an officer when a “rogue wave” struck and capsized the “24-foot fisheries enforcement vessel he was on, knocking Officer Charlie Cortez into the rough seas off the Tulalip Reservation. After a multi-agency search, joined by the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Navy, they did not recover Officer Cortez’s body. Cortez “and his partner had just escorted a distressed boater into Tulalip Bay…” before capsizing. Officer Cortez’s partner, suffering from hypothermia, was rescued by a nearby fishing boat.

Washington State Patrol Trooper Chris Cooper reported to Officer Down Memorial Page that he was working on a detail on March 26th, 2022. He said a young girl handed the troopers a sticker for the “end of watch” for Tulalip Tribal Officer Charlie Cortez #767 (badge number). Trooper Cooper said they were moved that this child wanted to make sure no one ever forgot Officer Cortez.

Again, this barely scratched the surface regarding the similarities and differences between cops in Indian Country and other parts of the United States. And while there are differences that make law enforcement on Indian Reservations both rewarding and uniquely challenging, the similarities connecting Indian and non-Indian cops are far greater, linking them as a part of the great brotherhood and sisterhood of American law enforcement.