Police canines and their human handlers have been making the news a lot lately—as well they should, especially for all the dynamo police work they accomplish on behalf of citizens’ safety. Yet there is a dynamic in police service animals that are hardly highlighted, one deserving of accolades for the care and compassion provided to our hard-hitting crimefighting animals: Veterinarians.

I came across such an example last night, whereby a long line of NYPD canine cops and their service dogs assembled outside Schwarzman Animal Medical Center to honor their long-term veterinarian highly known for dedication to ensuring the health and welfare of the largest municipal law enforcement agency’s contingent of police dogs.

In that context, thanks to the sentiments of the NYPD Transit Bureau cops who feverishly patrol the oft-heinous five-county subterranean system of noisy trains and spiked depravity, we witness a fond farewell to a tenured veterinarian who was instrumental in caring for police canines:

“When it comes to looking out for our 4-legged transit officers, Kathryn Coyne was second to none. Under her leadership at the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center [in Manhattan], our K9s received top-notch medical care so they can better serve all New Yorkers. We wish Kate all the best as she embarks on her next chapter.”

Dr. Coyne is a cherished and admired veterinarian whose career served many NYPD cops, most notably administering compassionate care for their canine partners.

(Retiring police dog veterinarian Kathryn Coyne. Photo courtesy of the Animal Medical Center of New York.)

Retiring as president and CEO of a world-class institution, Dr. Coyne practiced veterinary medicine among the over 130 veterinarians “providing the highest quality medical care across more than 20 specialties and services” at Schwarzman, the “world’s largest non-profit animal hospital.” Music to a police animal’s ears…but sort of too few and far between.

Not having the benefit of access to a facility such as Schwarzman, many law enforcement agencies dutifully endeavor to onboard a bona fide animal doctor to care for their cadre of police service animals. Thankfully, police-centric organizations assist in this regard…

The National Police Dog Foundation seeks out and maintains a registry of practicing veterinarians interested in providing healthcare for police dogs, emphasizing the unfortunate reality of law enforcement canines often needing emergency triage after arrest attempts culminate in either shot, stabbed, and drowned police dogs being rushed to veterinarians for salvation.

(Photo courtesy of the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine.)

The day I observed the NYPD canine unit honoring Dr. Coyne’s retirement, I also saw an exposé regarding a class attended by current/future veterinarians, first responders, lawmakers, and others, all encircling animal-clinic operating tables as tenured instructors taught the nuances of urgent and non-emergency care of police dogs.

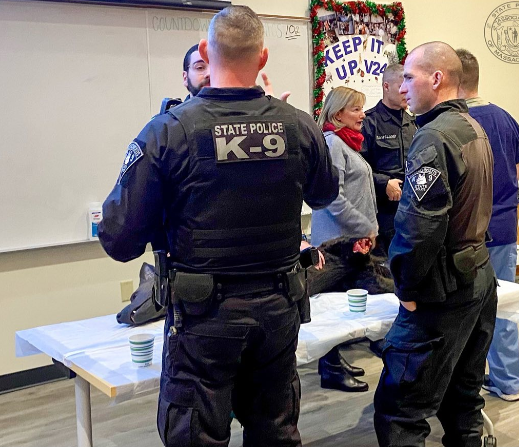

(Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts State Police Troopers.)

“Yesterday, Association Special Operations Troop Representative Michael Crowley and members from our K-9 Unit joined the first ever ‘Train the Trainer’ Class at Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine located in North Grafton, Massachusetts. This program was created for the Massachusetts K-9 Nero Law which has improved the medical care available for police K-9 officers across the Commonwealth.

“During this training, veterinary professionals and first responders learned improved first aid and advanced care for police K-9s needs.”

Nowadays, veterinary schools mention Nero’s Law (which the NPA covered when the statute was instituted) and how the statute honors our heroic police canines with the same due diligence given to human counterparts if/when exigent medical attention is necessitated.

Any eyes viewing these pages understand the National Police Association plays a significant role in granting ballistic vests custom-made for police canines throughout the nation. Each dog’s vest increases the probability that the canine, should they encounter criminal combatants seeking to harm or murder these four-pawed certified police officers, has a better chance of surviving such attacks by cold-hearted assailants.

Because of their size and vast jurisdiction, metropolis police organizations likely have the advantage of funds for police dogs’ healthcare and an ample presence of veterinarians from which to select provisions. Given most law enforcement entities in the United States are categorized as small, with notoriously modest means to finance police canine healthcare, how do they manifest veterinary care for their service animals?

As my agency did, basic budget allocations are supplemented by constant scouring for grant opportunities specifically designated for police canine units (purchase; training; medical costs; general maintenance/upkeep at the police handler’s house).

SpikesK9Fund is one source whereby law enforcement agencies can apply for monetary support toward healthcare for police canines.

Their website offers funding “for critical medical treatment to help [police dogs] return to work [after injury] or live their retirement days in complete health.” Spikes also offers courses in K9 Emergency Medical Care, so those in the field can commence lifesaving attempts of injured police dogs while prepping for transport to an animal hospital.

Naturally, there are way more veterinarian practices setting appointments to provide care for animals during business hours. There are fewer 24/7 animal hospitals. My department’s canine unit chose one from each category: one traditionalist for general veterinary healthcare and one 24/7 animal hospital in the event of a full-blown emergency (whether sustained on duty or otherwise), covering all bases for optimal canine care.

The National Police Dog Foundation invites “private practitioners, general and specialty, to join in with the Foundation to provide much-needed and genuinely appreciated veterinary care to law enforcement dogs nationwide.” Thus, via their organization’s registry, police executives and canine unit commanders sleuthing for a veterinarian to cater care for their dogs can tap them on the shoulder to ascertain if an animal doc is in their neck of the woods.

Circling back to the commentary giving birth to Spikes K9 Fund, one declaration stands out: “I think it’s important to understand exactly what we’re asking these dogs to do. If we’re going to ask them to take bullets or work really hard trying to find bombs or drugs or whatever, it’s really incumbent on us to take care of them and give them everything they need.

“We are there to help them with the damage that they’re going to sustain doing that kind of work for us. When there’s really violent stuff going on, the dogs save lives […] and we are safer as humans because of the work those dogs do for us.”

The succinctly sums up the purpose of this material, gives kudos to professionals who provide stellar care, and honors these working dogs that bravely bark at evildoers and nip it all in the bud.

Police canines earn the bones…veterinarians who care for them deserve the tributes.