Long before the current shouts for police reform, police leaders and trainers have been considering the efficiency of basic police academy training. Since the New York City School of Pistol Practice in 1895, which grew into a more generalized policy academy by 1909, there was early opposition to the need for training as the notion that prevailed for a long time was that all an officer needed was common sense and enough strength to swing a billy club.

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI training in the 1930s served as an inspiration for police training at all levels. The LAPD under Chief William Parker became a model professional agency in the 1950s after a major scandal when Parker emphasized rigorous pre-service and in-service training. Crime became a national political issue under the Presidency of Lyndon Johnson, with studies encouraging more education and training for officers with some money to help achieve it.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that all fifty states adopted minimum training standards. (As a Missouri officer this writer was hired before the state required police academy graduation. I was on solo patrol at age 21 after a three-week field training program, which was more than a lot of small departments got.) There are frequent movements to establish national training standards, but the history of independent, local policing and sentiments against the federalization of law enforcement have prevailed thus far.

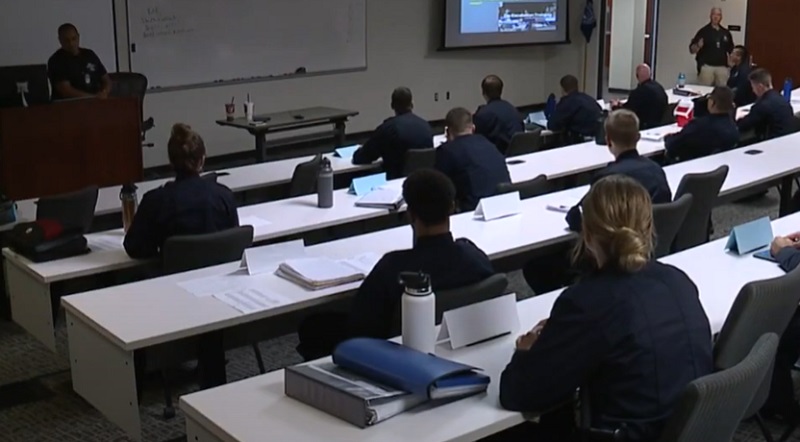

Training standards are up to each state, and individual agencies may exceed those standards. The two basic models of academy training are the paramilitary model and the collegiate model. The paramilitary model looks very much like military basic training. Physical fitness and mental toughness are emphasized. Cadets are placed under stress in highly formal structures. The collegiate model has a more academic approach with policing skills achieved through less formal means. There is no consensus on which produces a better law enforcement officer, and many – your author included – believe that the field training component after the academy when the rookie practices their craft under the tutelage of an experienced officer is the most important aspect of police training.

Pre-service training is available for eligible potential police officers who want to enroll in academy training before being employed and at their own expense. Most of these academies are on college campuses and are made up of self-sponsored pre-employed students and newly employed students on an agency’s payroll whose training is being paid for by their employer. Many agencies require a fixed period of employment commitment, with a promise to repay their training costs if the student leaves the sponsoring agency within a few years. This is to discourage having a small agency pay for certification training of an officer who immediately gets hired by a higher-paying agency.

Some law enforcement entities have an interest in perpetuating a unique culture that provides pride, unity, and status. These agencies eschew the blende academies in favor of having all cadets a part of one agency. For the sake of economy, some of these departments have accepted lateral employees from another agency with a shortened version for enculturation and agency-specific training, but the results have been mixed.

The irony of the demand for more training among police reform advocates is that some topics that have become politicized have been forced into academy curricula and displaced some of the traditional essentials of real-world policing. Defunding and budget shortfalls are often suffered most in the area of training.

For example, New York’s immigration crisis is being partly funded by Mayor Adam’s cutting the next NYPD recruit class, even with a 3,000 officer shortage since 2019 and a 30% rise in crime. The ongoing battle from so-called environmentalists against a new training facility in Atlanta, GA, has slowed progress toward better first responder training being demanded by other critics. Voters in Colorado Springs declined to fund a new training center that would have expanded recruitment and training capacity for an understaffed department in a growing city. In New Hampshire, the recruiting crisis has driven police executives to ask the state legislature to reduce or eliminate mandated physical requirements. In Portland, OR where vacancies have been high, newly hired candidates are waiting up to five months just to get into any of the state’s academies. In Massachusetts, a larger number of cadets already in an academy are quitting after losing the desire to become law enforcement officers. In Cleveland, OH, a city that is more than 200 officers short, the latest academy class had only 9 students, the smallest number in 25 years.

To all of those clamoring for police officers to get more training, it should be known that law enforcement leaders are trying, but the profession is taking a beating from critics and activists and budgets are taking a hit. Is this what the reformers wanted?