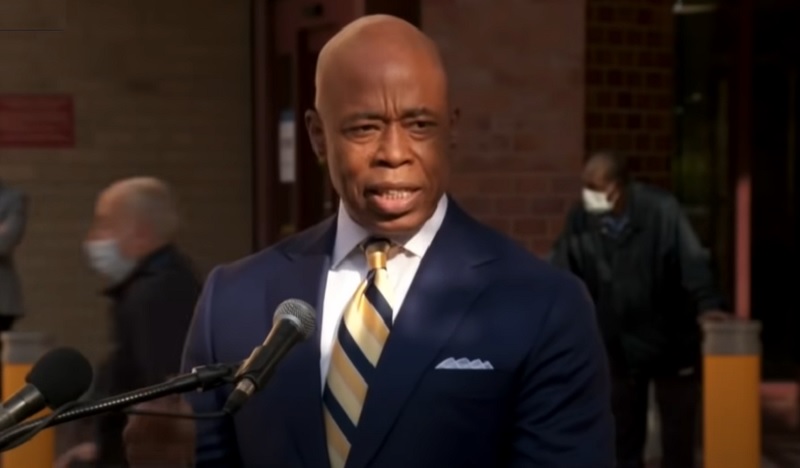

The practice of stopping suspicious persons to ask some questions and check them for weapons has never been illegal. It has been practiced in ways that has caused the courts to refine the practice, but not outlaw it. New York’s incoming Mayor Eric Adams is a retired NYPD captain, elected on a law-and-order platform that apparently appealed to New York voters fed up with rising crime and liberal catch-and-release enforcement policies.

The origin of the legal ability of government agents to detain citizens is the governing document of the U.S. Constitution. It states: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

These 54 words affirm that searches and seizure may happen, but that they must be reasonable and preferably done by warrant. Subsequent court interpretations recognized that there are situations where taking time to obtain a warrant presents a danger to the public or the officer. Therefore, one of the exclusions to the warrant requirement is an exigent circumstance, such as the reasonable possibility of a crime in progress. A reasonable search and seizure can still exist outside of a warrant.

Cleveland Police Detective Martin McFadden was patrolling in plain clothes in downtown Cleveland at approximately 2:30 in the afternoon of October 31, 1963. His attention was attracted by three men. The experienced detective saw the men pacing back and forth, conferring, and staring into a business in a way that led the detective to believe that a possible robbery was afoot. McFadden stopped the three, including John Terry, asked for identification and patted down their outer clothing, discovering guns in the coat pocket of Terry and one other. Based on finding them in possession of weapons unlawfully they were arrested. They appealed a conviction, claiming their rights were violated by McFadden’s search.

The famous case, known as Terry V. Ohio, finally decided in 1966, cemented the right of a police officer to briefly stop a person, briefly question them, and briefly search them for weapons. The case described the experience of the officer and the specific behaviors that led him to conclude that persons were possibly armed, and a crime was imminent.

It is important to note that a stop and frisk, known as a Terry stop, does not authorize random stops or stops based on mere suspicion. Without proper foundation, these stops are unreasonable under the 4th amendment. It has also become clear that using race is not allowed as a factor in determining whether a citizen will be contacted for a Terry stop.

An officer must specifically articulate not only the behavior they believe may be connected with criminal activity that justifies the temporary detention and questioning, but must also articulate why the officer believes a weapon may be present to extend the stop and questioning to a pat down search for weapons.

Incoming Mayor Eric Adams has said, correctly, that the question should not be whether or not police are allowed to confront suspects; it should be about how officers are trained. Stop, question, and frisk is a necessary tool for police to use to intercede in and prevent criminal activity. In the current climate, officers may be reluctant to engage in self-initiated activity, abiding by the cautious advice of “no contact, no complaint”. With more contacts resulting in non-compliance and resistance because of the anti-police mood embraced by lawbreakers, the potential for a contact escalating into violence is greater than ever. With the proper policy and training, as well as public education and support, officers may be able to confidently return to the active policing they want and need to do.