As mentioned in previous pieces, cops and community members can achieve remarkable objectives when they work together. Recently, a grassroots model transpired in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, New York.

Neighborhood Coordination Officers (NCOs) with the NYPD’s 73rd Precinct stationed in Brownsville were participants in a five-day pilot program whereby cops ebbed to the periphery of a two-block stretch on Mother Gaston Boulevard in December 2020.

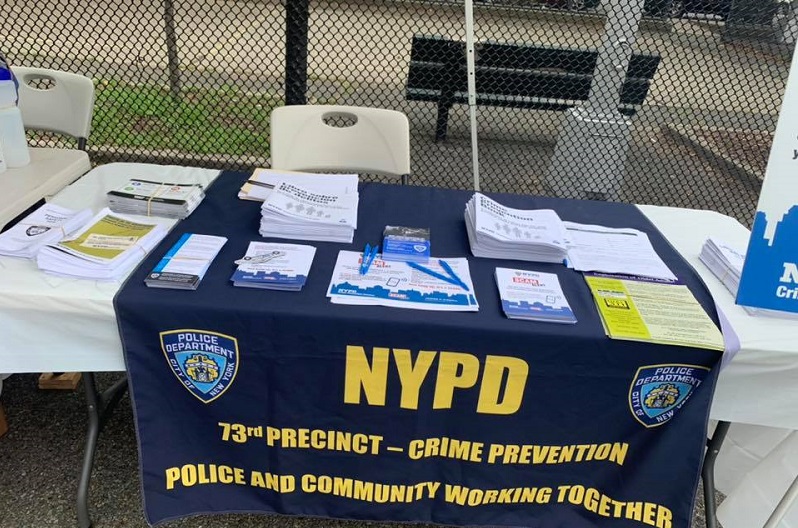

While NYPD cops were “nearby” and readied to respond should bad actors creep in and launch criminal misdeeds, civilians with the Brownsville Safety Alliance (BSA) sat at tables with informational pamphlets explaining social services and programs for area residents to take advantage of.

Founder of NYC Together, Dana Rachlin explained the “BSA is meant to replace traditional law enforcement interventions like steady foot posts and light towers with a community response & resources to address quality of life issues & crime. A key component is having Cure Violence organizations like BIVO [Brownsville In Violence Out] on the block to replace the police presence […] to serve this highly under-resourced and over-policed block.”

To provide some context to that previous statement, here are 73rd Precinct crime stats, including an historical scope.

The Safety Alliance designees trying to effect change in an area no stranger to violence/criminality call themselves “violence interrupters,” many of whom are classified as “community members with prior involvement with the criminal justice system.”

According to The City, a news source reporting on all-things-NYC, the violence interrupters aim to “prevent minor incidents from escalating into violence or other crime,” essentially the traditional role for which NYPD cops have been responsible. Sounds a lot like the oft-heralded Broken Windows theory which sought to suppress bigger community problems by addressing smaller ones, disallowing the fester of “minor” criminal acts so they do not morph into gargantuan ones.

The sorta in-tandem effort between NYPD neighborhood cops —whose credentialed purpose is to “spend all their working hours within the confines of their assigned sectors, actively engaging with local community members and residents” as “local problem solvers” who “get to know the neighborhood, its people, and its problems extremely well” —is designed to compliment civilian “violence interrupters,” especially since the goal is a mutual co-opt.

For a visual of the police-side of things, the following brief video is a sampling of the NYPD’s Neighborhood Coordination Officers, how effective they are in their respective community assignments, and the citizens who implore police presence:

Such a role in the NYPD’s roster of roughly 35,000 sworn cops is not necessarily new, only evolved over time. When I was growing up in a adjacent section of Brooklyn, the NYPD had what was then called the “Community Patrol Officer Program” (CPOP), an earlier derivative befitting the largely universal “Community Oriented Policing” (COP) modality contemporarily used by most of America’s 18,500 law enforcement agencies.

Self-evident by its namesake, the Brklynr —the “go-to source for Brooklyn news”— explored the evolution of CPOP and transference of the latest community-oriented policing concept known as NCO, which deploys beat cops walking the streets, inherently investing themselves by gleaning matters via their own instincts as well as intelligence provided by citizens residing in their sector (assigned beat). The mutual reliance serves to remedy woes and wrongs so as to ensure a more vibrant community by enriching citizens’ lives by establishing a safe environment.

Brklynr’s op-ed penned by Nathan Thompson and his expose on the NYPD’s legacy of community-oriented policing models portrays (among many salient points) one steady fact: beat cops wholly dedicated to specified small tracts of responsibility and not necessarily expected to zoom away when a 9-1-1 call is clearly on the opposite side of the precinct’s geography…equates to more personable service for either menial or major problems brewing and a prompt preempting of trouble(s).

Thus, the principle of police reform was in play years ago and effectively endeavored by NYPD administrators at One Police Plaza, carefully poring over statistical data conveying the needs of the community and calibrating re-deployment of resources to meet/exceed public safety deliverables.

Mr. Thompson’s Brooklyn-based experienced perspective touts “cops on the block” (as we used to say when I was a youngster, watching Brooklyn beat cops traversing the sidewalks in pairs, chatting with people, asking how we were doing in school).

Whether viewed as contrast or otherwise, The City reported that while the NYPD beat cops in Brownsville relented to “violence interrupters” for approximately 50 hours over five days, only one 9-1-1 call came in (reportedly a misdial caused by a city bus driver). If factual, that is great; both residents and cops can be elated by that. After all, the overall idea is public safety, an ideal just about everyone (the only exception criminals) seeks to embrace.

The City reporters cited, “…while the Brownsville Safety Alliance experiment was limited —covering just 50 daytime and evening hours during a cold week in the middle of a pandemic— elected officials and community leaders said it marked a significant step toward reimagining public safety.”

New York State Assemblywoman Latrice Monique Walker (D-Brooklyn) said, “This was ‘defund the police’ in actuality.” She also noted that “cops were stationed nearby and available to respond as needed” and that “the pilot indicated that a visible police presence isn’t essential to keeping the peace.” Criminals may be warm and fuzzy with that declaration.

Good thing the police do not see it as a competition, only a victory for the community they serve.

After all, “the cornerstone of today’s NYPD is Neighborhood Policing, a comprehensive crime-fighting strategy built on improved communication and collaboration between local police officers and community residents,” the NYPD explained while simultaneously confronting the stark reality of NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio slashing approximately $1 billion from the police budget.

Nevertheless, NYPD Deputy Inspector Terrell Anderson had this to say about the initiative involving the 73rd Precinct he commands: “I’m learning through working with different organizations how to be a better commanding officer and how to help my cops be better police officers as we move toward a future of reimagining public safety.” Again, no one wants to go it alone; criminals are extraordinarily opportunistic and have fewer chances to victimize when communities of cops and citizens work together.

To bolster the neighborhood cops’ efforts to satisfy community needs, the NYPD launched an app called “Build the Block” whereby residents can ascertain the locations of meetings hosted by boots-on-the-ground police officers assigned to their streets, enabling open forums regarding any community concerns, needs, innovations, and all manner of cohesion between cops and residents coexisting in any given area encompassing the NYPD’s 77 precincts spanning five boroughs (counties).

Besides residents, the pulse on public safety officials often is best conveyed by merchants who have their lives invested in a business and harbor fears of criminal elements storming in and ripping all that away by either armed robbery or burglars looting inventories under cover of darkness.

Proprietor of Aida African Hair Braiding Salon, Ndeye Thian told the press that she “feels safer doing business on Mother Gaston Boulevard with the police in sight.” In the same breath, Ms. Thian offered, “If I open this store and make my dollar, I’m happy. We don’t need the police to watch us all the time.” Fair enough. Sounds a lot like what we have been witnessing lately: the heavily emphasized anti-police movement perpetuated by certain politicians and citizens decry law enforcement presence…until they exigently need cops as post-victimization sources of salvation.

Doors away from Ms. Thian’s salon is Brownsville Bike Shop owner Cleveland Smillie, 68, who offered the following sentiment: “If there’s not police on the block, I can’t open the store.” Operating his bike business for 37 years, the almost-four-decade modest build-up by a merchant fearing a thug walk in and destroy it all is palpable concern with credible worry, hence the importance of police presence to preempt such a nightmarish scenario from spawning.

John Jay College of Criminal Justice research director Jeffrey Butts noted the Brownsville pilot program and cautioned the messaging, saying, “…you don’t want to communicate to the community that we’re no longer protected by law enforcement.” In short: criminal elements salivate over such a possibility, further endangering law-abiding citizens trying to make it in the world.

Backing up the assertion made by Mr. Butts, Jerry Ratcliffe, Temple University professor of criminal justice studies, said the following: “You can withdraw patrol policing from a couple of blocks, but that doesn’t mean the police have disappeared. They’re still pretty much seconds away if anybody calls and they’re very likely patrolling the areas that people [use] to get to those two blocks.”

Those were my thoughts before I even read that NYPD cops ebbed a few streets away as “violence interrupters” set up shop on the sidewalks.

Program director for Brownsville In Violence Out (BIVO), Anthony Newerls feels “the [police-community] partnership is what makes the system work. I don’t think you can have one without the other.” Respectfully speaking, it’s always been about those elements. Like those of other cops, my police career was stapled on community relations, from which viable intelligence generated actionable operations to thwart bad ingredients from victimizing innocents.

Whether folks desire cops in proactive or reactive mode, the common denominator is they are there and they are going to fulfill their duty.

Just as Democrat Assemblywoman Walker boasts about the Brownsville pilot program having a fortunately uneventful test-run, it seems a counterpoint is definitely equitable. We sew up our analysis with the following real-life example of a Brooklynite whose child wandered away and got lost in a sea of parade revelers. Especially as it relates to our subject matter and police presence in the community, Mr. Thompson revealed the following carefully weighed nugget:

“Years ago, my wife took our five-year-old son to the Mermaid Parade. He slipped out of her hand and was lost in a sea of 20,000 marchers. She asked a police officer for help.” In due time, NYPD blues delivered on their promise to protect and serve

“’We have Alex. It’s on the [police] radio,’ the officer explained, adding, ‘Your son was very comfortable with the uniform. He knew he was lost and he picked an officer’s uniform out of all these costumes to approach and explain his problem. We guessed you had an officer in the family.’

“In a way, he was right. This is how the next generation could see police officers. CPOPs or NCOs (or whatever you want to call them) like these, we need now more than ever.”

So, a little lost soul frighteningly wandering among throngs of costumed people…knew enough to home in on the blue badged uniform worn by Officer Friendly who would make things right in his world, rejoining him with his mom and dad.

As mentioned, cops are always in the community on behalf of the community…and they are going to exemplify the public service mantra when called upon.

We are reminded of the poignant wisdom-ripe words spoken by President Ronald Reagan: “Where did we find such men [and women]? We find them where we’ve always found them. In our villages and towns. On our city streets.”