By Steve Pomper

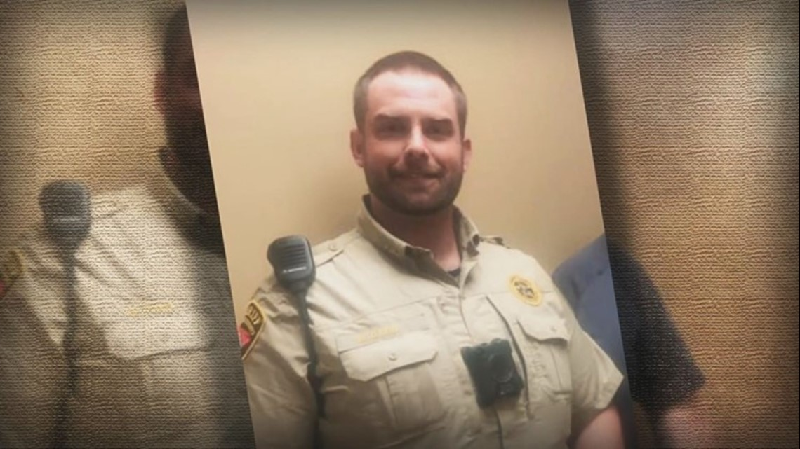

On June 23, 2021, at about 3 a.m., Sgt. Michael Davis, a nine-year veteran of the Lanoke County Sheriff’s Office, stopped Hunter Brittain and two passengers. The AP reported, according to Davis, Brittain quickly got out of his truck and reached into the bed of his pickup.

Sgt. Davis said he told Brittain to “show his hands,” but he didn’t do it. Why would Brittain get out of the truck and dig for something in the pickup bed? Why would Brittain refuse to obey a deputy wanting to see his hands?

Am I saying for sure that’s what happened? No. I don’t know for sure what happened; I wasn’t there. But the sergeant’s version of events seems to be better evidence of what happened than the officer shot a teenager “for no reason.”

I’m not even saying I would have done the same thing the sergeant did. I can only hope I’d make honest, good faith decisions that would get me home to my family after shift. What the sergeant says he did sounds reasonable under the circumstances he describes. How long would it take for a suspect to pull out a gun, if that’s what he was digging for?

Though this is not an exact situation, this video shows just how fast things can go wrong when an officer loses sight of a suspect’s hands (warning: the images are graphic and unsettling).

Sgt. Davis gave a “nutshell” version of events to detectives. As reported by the Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Davis had passed Brittain’s car, which appeared to be having mechanical problems.

At first, Davis says he thought the smoke near the car was fog, then he said, “‘It was making a loud racket. Clearly, there was [sic] some car issues,’ Davis told an investigator.” He said the smoke was so heavy, he couldn’t read the license plate.

The report continued. “‘The deputy turned on his lights after following for a short distance. Brittain’s vehicle crossed into the oncoming traffic lane, stopped and then revved before turning into the body shop,’ he said.”

“At this point in the interview Davis took a long sigh. He paused. When he started talking again his voice was shaky with emotion.

“‘Before I could get the vehicle in park the driver jumps out and slides,’ he said.

“Davis said he told Brittain to get back in the vehicle, to show his hands and to stop. He said Brittain didn’t comply. He said Brittain had his hands in the truck bed, digging.

“‘And I shot him,’ Davis said.”

According to U.S. News & World Report, “A passenger and another witness testified they never heard Davis tell the teen to show his hands.”

I don’t know what happened during that early morning incident. But during my career, I can’t count the number of times the very first thing I (and every other cop I know) said was, “show me your hands.” Cops have the phrase indelibly stamped in their brains. Hands hold weapons that can hurt or kill them.

I can’t say for sure the officer said those words. But I can offer my real-life experiences to those who don’t know police work.

Cop-haters, and even more restrained cop-critics, seem to assume the worst about an officer’s actions. Davis was fired for was not turning on his body camera until after the shooting in violation of department policy. Was this intentional? I don’t know. As I said, I wasn’t there. But I don’t believe he knew he was about to shoot someone.

But, except for Davis and the witnesses, no one else talking about the shooting was there either. And, being in the vehicle, the witnesses would have limited views of what happened outside the truck.

And they sure couldn’t know what Davis was thinking while making split-second decisions. He’s watching for Brittain’s hands and trying to keep an eye on the passengers at three in the morning.

To relate to an officer forgetting to turn on his or her body cam, think about your job. Do you ever forget to do something, even if you do it all the time? Did you forget to do whatever on purpose? Was it a life or death situation?

Davis’ version just rings true to me. In a recent NPA article, I wrote, “Whenever I write stories like this, I always look out for that “hold up” moment if I run into information that causes me to hesitate.” Now as then, based on what I read, I’m just not seeing that moment. I’d have to deny the officer the benefit of the doubt to believe what the prosecution alleged happened. Davis had seconds to make his decision based on what he saw at the time.

I’m giving the officer the benefit of the doubt his oath earns him unless credible evidence says otherwise. When writing about such incidents, if I didn’t believe the officer’s account, I wouldn’t whitewash it to make dubious actions seem okay. I simply wouldn’t write about it at all. I’d move on to a story without a “hold up” moment. There are enough people out there writing nasty things about cops. Cop-haters don’t need any help.

With this verdict, is society saying, even if a suspect won’t obey officers’ orders to show his hands, while digging around in the bed of a pickup at 3 a.m., an officer must bet his or her life he’s not digging for a weapon?

The jury acquitted Davis of manslaughter, a felony punishable with from three to 10 years in prison. But the jury convicted him of the alternate lesser offense of negligent homicide, a misdemeanor with a one-year sentence and a $1,000 fine.

As Davis’ lawyer alluded to, juries sometimes choose the lesser offense if it’s offered. Seems like a way to “split the baby” when jurors don’t want to be seen as “too pro- or too anti-law enforcement.” Each side gets and loses “something.” They may also believe, if they’re “compromising,” that an appeals court will “fix the mistake” later when emotions have calmed.

That’s not how it’s supposed to work, but that’s sometimes how it works.

Of course, the family is upset, even understandably angry. They don’t know police work any more than political anti-cop activists do. Society doesn’t do a very good job of teaching people what cops face doing their jobs. However, the victim’s family’s pain and grief are real. I hope I could be objective if it were my family member, but I honestly don’t know. However, non-loved ones should use reason and not emotion to judge police actions.

Davis is free on bond, pending appeal.