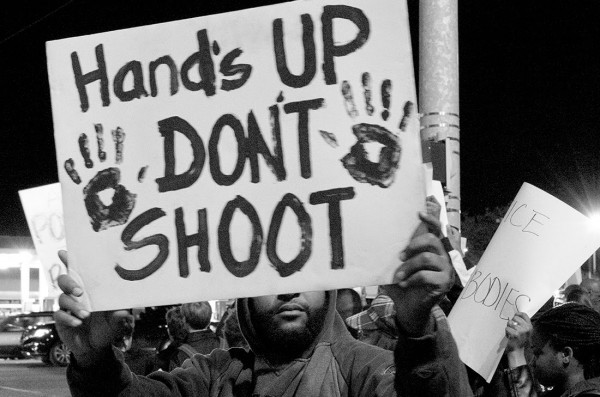

The chant of “Hands up, don’t shoot” echoed in the streets of protests across the country after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. In the immediate aftermath of the false narrative that caught fire on social media faster than the torched convenience store in town. No official voice outperformed Twitter in the hours after the shooting, and the hours and months of multiple investigations that determined the shooting was lawful and justified have never outperformed to the false narrative that still lives in rhetoric today.

Even though the fable that Brown had his hands up in surrender has been soundly refuted, the idea that an officer is safe at any point during an apprehension is also untrue. FBI studies on officers assaulted reveal that the moment of surrender or handcuffing is one of the most dangerous activities for officers.

According to television and movies, three things happen with an offender who is being arrested. One is that they are shot, the other is that they submit to arrest and get handcuffed and escorted away, and thirdly they engage in a brief struggle until the officers get them under control. A fourth thing that can happen, seldom portrayed, is that the suspect can initially appear to comply but then resist and assault or attempt to assault the officer.

There are several reasons why this is a flash point for assault. One is that the officer may be so relieved that the suspect has given up, that they let their vigilance lapse and are psychologically and tactically unprepared for a fresh wave of resistance. Secondly, any time an officer gets within arm’s reach of a suspect they bring their weapons systems with them which are vulnerable to attack. A tricky suspect, calculating the risk of prison relative to the risk of escape, is tempted to go for the officer’s gun, pepper spray, baton, or Taser, or to apply a kick or punch to a vulnerable body part. Thirdly, many suspects are under the influence of mind-altering chemicals that can incite erratic behavior and sudden mood changes from submission to attack.

A fourth reality is that apparent submission or even successful application of handcuffs is no guarantee that the danger is over. Prison surveillance video shows inmates practicing escape and attack tactics. They have plenty of time to practice and plenty of incentive to use those skills when they get back on the street and resume their criminal lifestyle. Head-butting, kicking, and grabbing can all still be accomplished while handcuffed. Those who practice, don’t mind the pain, or have unusual bone structure, can manage to get out of restraints and wait for a moment of distraction to attack the officer. Having one handcuff free makes a formidable weapon itself.

While the average citizen can’t fathom why a suspect would assault an officer and face certain capture and more severe punishment, the reality is that assaulting an officer is often free of consequences for an offender. Assaults on officers are among the first charges pled or dropped where other felonies are pending. Some officers don’t even spend much time reporting assaults on themselves since their hope of prosecution or restitution seems dim. Criminals facing serious charges are looking at prison time regardless, and can easily figure that an attempted escape or hurting a cop won’t make that much difference.

Finally, what is seen on video by critics and Monday morning couch coaches that might look like unnecessary force after an arrest, may not reflect what the officer sees. The flick of movement toward a weapon, the glance of the eyes toward an escape route or confederate, or the refusal to show their hands can be danger warnings that escape the civilian eye. In one notable case, an officer was criticized for shoving a handcuffed suspect against the hood of a patrol car. A close examination of the video, however, showed that the suspect handcuffed behind his back, had grabbed the crotch of the officer and was squeezing the officer’s testicles painfully until the suspect was shoved forward.

A suspect doesn’t cease to be a threat to the arresting officer and the public at large until they are safely behind bars. As Yogi Berra famously said: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”