Radio codes vary from agency to agency, but most I’ve been around use Code 4 as “everything is OK”. That doesn’t really mean that everything is ok, it just means that for the moment, as far as the officer on the scene can tell, nobody is trying to kill anybody. For the men and women behind the radio consoles, seldom is everything Code 4.

I was slow getting educated on the effects of constant trauma exposure in emergency services. Maybe I was cold-hearted, maybe I have a strong constitution, maybe I didn’t expect anything but trauma and therefore wasn’t surprised by anything. Years ago I was knocked unconscious on a traffic stop. After leaving that agency I ran into the dispatcher that was on the night my partner radioed in “officer down”. In the course of reminiscing, she mentioned that night, describing it as one of the worst nights of her career. I am ashamed to say I had never considered the effect of that event on my dispatcher.

There are several reasons why dispatchers have unique stresses. One reason is that they do not have the balance of vision to perceive what’s going on at the other end of the telephone or microphone. They must interpret the scene with only the cues of noise, silence, and the tone of overheard conversation. Over time, their skills at understanding what their officers are or will be facing by the variance heard in voices is nothing short of amazing. This is especially true when it comes to knowing officers that they work with regularly. Some officers’ voices reach a high pitch under stress, others actually speak more slowly under stress. A dispatcher may know the officer needs assistance before the officer knows.

Another reason is the vicarious stress that dispatchers hear constantly. Whether their calm voice reveals it or not, pulse and blood pressure rises in sympathy with an officer in hot pursuit, calling for help, or describing injuries for arriving medical units. They are not emotionally disengaged no matter how hard they try. They are often monitoring several agencies over several radio channels in order to maintain awareness about the availability of responders and what scenes might spill over to others. Each urgent piece of radio traffic signals their brains to get ready for trouble.

A third reason that stress is unique to the dispatcher is that they have limited control over their calls. While anticipating needs at the scene and following requests by officers present, the ultimate outcome is out of the dispatchers’ hands. Dispatchers recognize their critical and life-saving role but realize that they will be miles from the event and rely on information relayed to them. A feeling of helplessness can be present during an event, even with the knowledge that they are being very active in the situation.

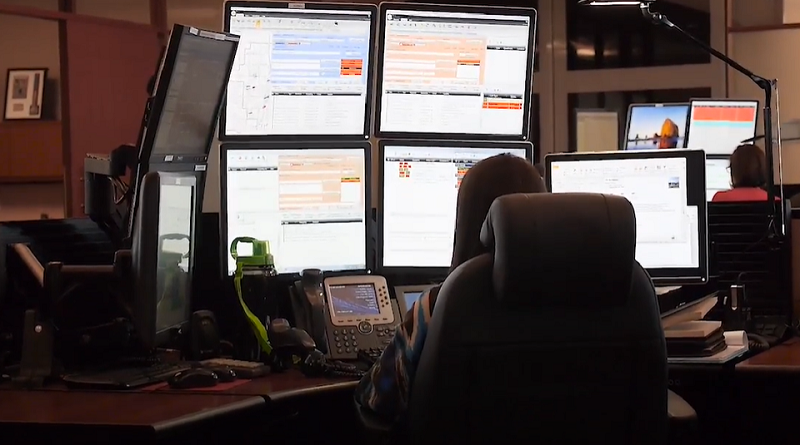

A fourth reason the dispatcher’s stress is unique derives from their superpower of multi-tasking. This writer was cross-trained as a dispatcher and can testify to the barrage of responsibility facing each shift. I never mastered the speed and automatic reactions that dispatchers develop because I only sat behind the radio rarely to fill in for absences. On one of my first nights, one of my fellow officers was in pursuit of a motorcycle that ended in the cyclist’s crash. This required an EMS response, a supervisor, and running the operator and motorcycle through multiple computer databases. At the same time, I got a call of a fire under the jurisdiction of our rural volunteer fire department. This meant setting off pager tones and answering multiple radio inquiries from volunteers not particularly skilled in radio discipline. At the same time, a call came over the CB (we were monitoring Citizen Band radio during that era) reporting a burglary in progress that the CB operator was narrating play-by-play to me. Please, God, put me back on patrol!

Another stressor to be noted is the sedentary nature of the job. While other first responders can burn off their adrenaline by working a scene and being very physical, the stress experienced by the dispatcher has no outlet and no on-duty opportunity to regain normal blood chemistry. Working long shifts with limited break time (if they’re lucky) is not conducive to a healthy diet either.

There are plenty of other risks to dispatchers in terms of their mental and physical health. They are often left out of services that are afforded to other emergency workers after a traumatic event. If a dispatcher works a call with a death involved, they feel the loss but are sometimes left out of the inner circle of care that the other men and women in uniform are provided even though they may have listened to a dying person’s last breath.

Dispatchers are truly the lifeline between a frantic caller and help that is on the way. They deserve all of the professional respect, compensation, training, and care that they can get.