We don’t often hear about Indian Reservations and the often-remote tribal police departments whose jurisdictions are deemed federal lands…until a line-of-duty death (LODD) occurs.

On June 2, 2022, a White Mountain Apache Police Department officer in rural eastern Arizona stopped an automobile. Reports indicate the motorist and the tribal police officer engaged in an altercation. The tribal cop was shot and killed. (This is the second White Mountain Apache PD officer shot and killed in the line of duty since the prior one in February 2020.)

According to preliminary reports, the suspect abandoned his car and stole the White Mountain Apache Police cruiser, leaving the tribal cop to die on desolate terrain.

After a police pursuit ensued, coursed through Fort Apache Indian Reservation lands, and came to a halt some 40 miles later, tribal cops engaged the shooter. In the gunbattle, a back-up tribal officer was shot and subsequently flown to a Phoenix-area hospital. That officer is reported as in stable condition.

The gunman was killed in the exchange of gunfire with tribal law enforcement officers.

Initially, the Navajo County Sheriff’s Office (NCSO) was the law enforcement agency leading the investigation.

NCSO posted a press release with details of what transpired, saying, “An altercation occurred between the officer and the person operating the vehicle. During the altercation, the officer was fatally shot.”

(Google Maps.)

In remote regions, law enforcement protocol is generally to back-up other officers as a matter of routine. It sounds like this was the case, placing back-up in the vicinity to engage the armed suspect.

A news source in Arizona stated the police were able to “track the stolen cruiser.” This detail indicates the policer cruisers may be equipped with GPS tracking devices employed for locating cops who are not responding when summoned via radio traffic (routine matter during traffic stops). Monitored by police dispatchers at police HQ, computer screens geo-track the locations of the fleet of cruisers on the roadways. Geo trackers also help in properly assigning patrol officers deemed closest to locations of calls for service.

(Photo courtesy of the White Mountain Apache Police Department.)

Installing vehicle location technology seems a requisite feature for cops to have, especially those who patrol remote regions. To punctuate the point, the nearest medical examiner in Pima County has the responsibility of nine counties, according to ABC News affilitate KGUN9.

As mentioned above, we do not usually hear about Indian Reservation law enforcement, except when it is dire. In this case, the line-of-duty death of White Mountain Apache Police Department Officer Adrian Lopez, badge P219:

(Photo courtesy of the White Mountain Apache Police Department.)

Like railroad cops and campus police, tribal law enforcement is classed as “specialty police” responsible for unique challenges in public safety.

Governed by the U.S. government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), constituted under the U.S. Department of the Interior, Indian reservations are accorded sovereign jurisdiction under federal code.

The BIA’s Office of Justice Services (law enforcement) mission is “to uphold Tribal sovereignty and provide for the safety of Indian communities by ensuring the protection of life and property, enforcing laws, maintaining justice and order, and by ensuring that sentenced American Indian offenders are confined in safe, secure, and humane environments. Ensuring public safety and justice is arguably the most fundamental of government services provided in Tribal communities.”

Tribal reservations are sometimes referred to as “Indian Country” governed by federal statutes as follows:

- Formal [recognized treaty boundaries] & informal [Tribal trust lands] reservations (including rights-of-way/roads),

- Dependent Indian communities & Indian allotments held in trust or restricted status (including rights-of-way/roads).

- Where no congressional grant of jurisdiction to state government over the Indian country involved exists.

Tribal police agencies and respective law enforcement officers derive federal jurisdiction via U.S. statutes granting authority to “enforce laws, including detention of offenders,” as dictated in the Indian Law Enforcement Reform Act and the Tribal Law and Order Act.

The Indian criminal justice system operates its own courts, governed by the Tribal Justice Support Act.

In general, the BIA Office of Justice Service’s infrastructure consists of uniformed police officers “responsible for patrolling designated service areas and responding to a wide range of calls for service. Criminal Investigators are primarily responsible for conducting investigations of criminal activity, and Dispatch personnel function as the critical communication link between the public and emergency response personnel. Together, these three programs represent the law enforcement component of justice systems in nearly 200 Indian communities.”

In that context, tribal police encounter what non-tribal rural law enforcement does: remoteness. As any law enforcement officer anywhere can tell you, when things go bad in desolate terrain, police training is the most immediate back-up (instrumental factor when the human brand is not on-scene yet).

Putting some numbers (tax dollar implications) to this discussion point, the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Systems “funds just over 800 federal positions and twice as many Tribal positions to help address the public safety and justice needs of tribal communities each year.”

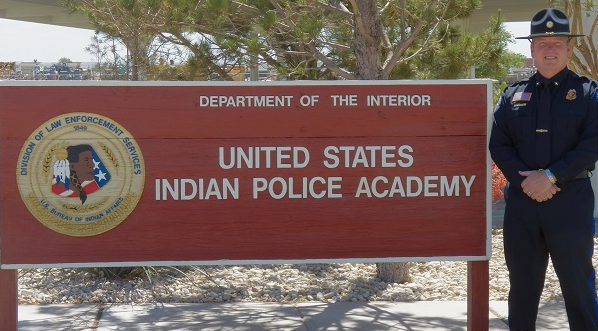

Naturally, none of this is possible without law enforcement training. Although the alphabet soup of federal law enforcement agents train at designated facilities (FLETC), prospective tribal cops train at the Indian Police Academy located at the Department of Homeland Security Federal Law Enforcement Training Center at Artesia, New Mexico.

(Photo courtesy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Police Academy.)

There, tribal police recruits are trained in “basic police, criminal investigation, telecommunications, and detention training programs” for personnel “serving both direct service and Tribally operated BIA funded law enforcement programs.”

As well, advanced courses are offered in child abuse investigation; domestic violence investigation; sex crime investigation; field training officer certification; management/leadership; peer support/critical incident debriefing; community policing; and drug investigation, all funded by “the IPA’s budget and offered at no cost to tribal and BIA public safety personnel throughout the year.”

Sometimes, we may be exposed to jurisdictional boundaries involving tribal law enforcement and non-tribal cop cohorts such as state troopers, county sheriff’s deputies, and municipal police officers—I recall this coming up in law classes while studying at the police academy.

Given the federal jurisdiction of every tribal police agency, in the line-of-duty death described above, the initial primary investigating agency (Navajo County Sheriff’s Office on behalf of the federally authorized White Mountain Apache PD) transferred all of its cursory findings to the FBI, which will assume/continue the overall investigation. (Had the cop-killer lived, he’d have been federally prosecuted in Indian courts.)

This is the relative protocol when a law enforcement agency is impacted by line-of-duty losses. The next rung in police authority hierarchy assumes the investigation with objectivity —in this case, the Navajo County Sheriff’s Office, until the duly recognized jurisdictional authority (the FBI, due to federal domain under the BIA) arrives in the remoteness and assumes investigatory responsibility.

Agencies of all levels can and do work together, despite stereotypical insinuations often propped up in bygone eras. (In my career, I’ve never met any higher authority who threw that chip around. After all, everyone wanted justice, and that is best achieved by minds concentrating together.)

Via Navajo County Sheriff David Clouse, the White Mountain Apache Tribe said it was “indebted to our Police Department and EMS for their prompt and courageous response, and grateful for the assistance rendered by our neighboring jurisdictions.”

No matter how rural and desolate the landscape may be, the Thin Blue Line is unfrayed. This tragic incident, culminating in the loss of a law enforcement officer and the hospitalization of another one, underscores the perils out there and the public safety professionals who step up and assume the battles against evil…no matter where it lurks.

In that context, a collection of courageous members from various law enforcement agencies responded to help. The list includes White Mountain Apache Game Rangers, Apache County Sheriff’s Office, San Carlos Apache Game Rangers, Pinetop-Lakeside Police Department, Arizona Department of Public Safety, and, ultimately, the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

With the line-of-duty death of White Mountain Apache Police Officer Adrian Lopez on June 2, 2022, his name will be beveled in granite at the Indian Country Law Enforcement Memorial.

As The Rural Badge echoed, “Mayberry is a myth.”