Although technology is prevalent in modern-day policing, some old-school methods remain as pointed as a sharpened pencil. Police sketch artists putting pencil to paper were all the rave back in the day, well before the tech we have nowadays.

Yet some law enforcement agencies retain the antiquity of a police sketch artist armed with a graphite pencil to help generate suspect imagery via victim/witness accounts of what the assailant looked like.

I was reminded of the concept when I came across two police sketch artists (aka forensic sketch artists) employed by the New York City Police Department. Each artist is or was a sworn police officer. Although customarily armed with a firearm, the NYPD sketch artist’s weapon of choice to get their man or woman is a graphite stick tipped with an eraser.

Sighting these recent examples of time-worn methods in policing transported me back to the day I aspired to be exactly like them. Drawing since age five, I aspired to be an NYC cop specializing in constructing hand-drawn images to disseminate to the troops and feed to the press for broadcast. Remember the over-the-shoulder mug shots portrayed during morning or nightly news segments?

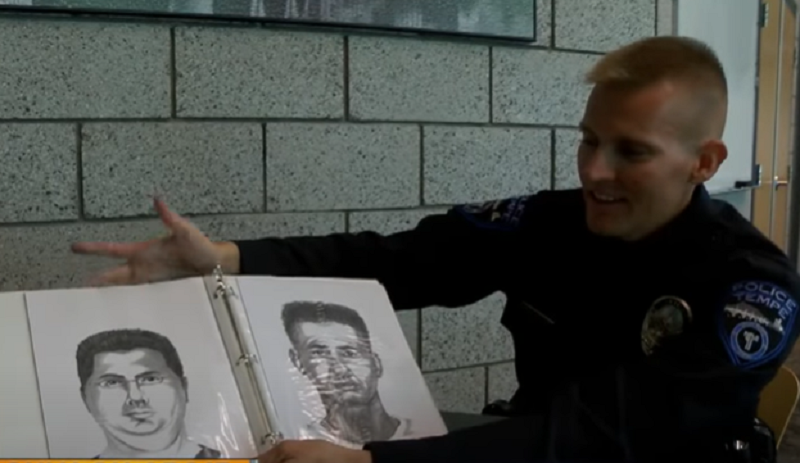

Changing from NYPD blue hues to desktop shades of gray are artistically inclined police officers (notice the recognizable portraits over the cop’s shoulder) assigned to the Latent Print Section’s Sketch Artist Unit.

One noted talent is police sketch artist Matt Klein, a detective employing his skills to identify suspects from victims and/or witnesses describing attackers’ facial anatomy.

As you just saw/heard in that brief video, pencils do the deed for Detective Klein and colleagues needing to place a face to the crime(s). Out of 35,000 NYPD cops, only a few are selected to be full-time sketch artists! Per a 2016 New York Daily News article, there were “only about 100 full-time forensic artists in the United States, plying a throwback trade that relies on the skill of getting often-traumatized people to open up and talk about a horrific crime.” Det. Klein is one of them.

I did notice a digitized drawing device and a pentel in that video montage. Detective Steve Fusko with the Orange County, Florida sheriff’s office forensic artists initially pencil-sketches suspect composites then refines them in a software program:

One can imagine the necessary repose in indulging the painstaking process surrounding the delicate nature of people providing the crucial details and nuances—both Detectives Klein and Fusko touched upon this.

Cases involving distraught victims coming into the precinct building, with all its hustle and bustle, surely require a quiet zone with one-on-one counseling of sorts. Victims recounting their criminal event means they may relive the trauma, defeating the purpose of producing a suspect on paper. Interpersonal skills to the rescue…

Besides being skilled in portraiture, police sketch artists lean in on their interviewing abilities, making the information source as comfortable as possible; a calm mind relates to better concentration.

As the Los Angeles Times once published, “Memory also erodes under stress, and a crime victim sitting across a table from a police artist is often under strong and conflicting forces. On one hand, he may feel pressure to remember details, believing that the capture of a criminal is riding on the precision of his description. And at the same time, he may be unconsciously trying to repress the traumatic memory of the attack.”

Mentally walking/talking a victim through the tragic details —not quite hypnotic, but close to that realm— is offset by rapport.

Victims and/or witnesses to criminal events experience additional nerve-wracking when shown the proverbial mugshot books. In my career, I’ve seen plenty of survivors go through binder after binder of criminals depicted in non-photogenic forms; scowling at the camera lens seemed the norm. Cold, dead eyes are in many pictures.

People may visit detectives several times before they muster composure to help identify assailants.

The sifting-through-mug-shots ordeal is supplanted by the one-to-one concept of a police sketch artist and a victim (or witness), concentrating on a solitary suspect instead of viewing hundreds in police photo albums.

From a psychology standpoint, imagine being in the unenviable position of staring at scores of bona fide malfeasants while flipping through reams of pages loaded with their mugs—devils in details.

Piecing it Together

One other method of forming suspect imagery is via the use of acetate sheets, upon which are human facial features; when stacked in overlay fashion, they form a face and are confirmed by a victim or witness as “the one.”

After phasing out photo albums, the overlay method was used by my department. During stints of light-duty, I seized the opportunity to see how our Criminal Investigations Division detectives patiently and delicately consoled frazzled citizens recounting a criminal event, invariably tapping their memory bank for details about the suspect(s).

One of our seasoned detectives happened to also be a licensed psychologist, with a forte in hypnotherapy. His brand of patience complimented by an unwaveringly low octave seemed to almost sedate the skittish folks trying to convey pertinent details. It was impressive to observe, and it worked every time—a skill within a skill. As mentioned in previous material, cops are a resourceful bunch.

In essence, each overlay looks like a hand-drawn facial feature (eyes, ears, lips, chins, scars, tattoos, hairlines, brows, noses) permanently inked onto the clear acetate surface. Sheets of solid tints were used to create proper pigment.

As the describer conveys specific dynamics of the bad guy’s face, a detective quietly inserts corresponding overlays, piece by piece, forming the compilation of a face belonging to the bad guy. It takes time but gives cops something to go on.

We knew we were close when the victims glared at a match made from a stack of plastic sheets, each slice depicting a facial aspect. Their heads bobbing up and down, staring at the finished element, was tacit affirmation. Some cried when we were done. Relative closure, I suppose.

Finals were reproduced and distributed to patrol officers. As well, neighboring police agencies were provided copies of Wanted suspects, a brief bio with the case number(s) attached.

Putting Suspects to Paper

It may come down to a dental observation which, when rendered by a police officer with pencils, ultimately leads to apprehending the bad guy.

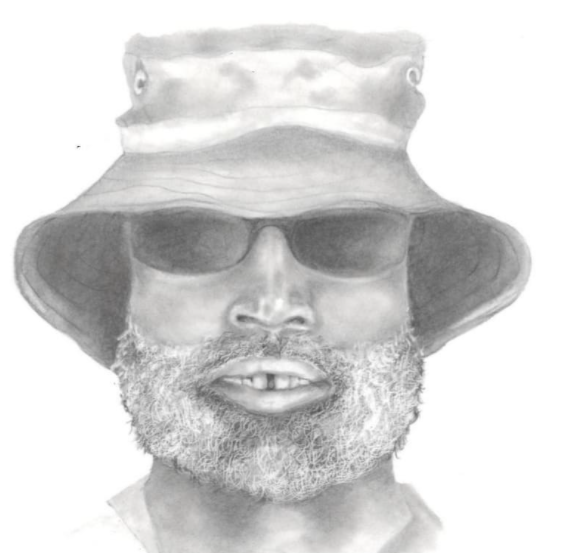

(Photo courtesy of the Las Vegas Metro Police Department.)

Accompanying the police sketch artist’s pencil rendering was the following narrative:

“On June 20, 2019 at approximately 10:53 a.m., patrol officers responded to the 7200 block of West Alexander Road to investigate a sexual assault. Officers learned that the victim drove her vehicle to Bunker Park before going for a run. While jogging, she observed an unidentified black male holding a drill and wearing a construction-type reflective vest standing by a Conex box. As the victim was walking back to her vehicle, the suspect came up from behind and pushed her to the ground. The suspect threatened the victim with a box cutter and then proceeded to sexually assault her.

“The suspect is described as an older black male adult, 6’02’’, thin build, bushy grey or salt and pepper beard, and a gap between his front teeth. He was last seen wearing a tan fisherman-style hat, charcoal grey long sleeve shirt, green cargo pants, and yellow reflective construction vest.”

According to the Las Vegas Metro Police, their sketch artist produced the image above, leading to the suspect’s arrest two days later.

Even though police sketch artists are considered old-school, this traditional method carries on. I discovered that many police sketch artists, most of whom had careers as sworn LEOs, retired and subsequently returned to pick up the pencil and get forensic.

Now working for the Baltimore Police Department, media stations produced a piece on Michael Streed and his infamy in helping catch deviants after composing pencil sketches virtually dictated by victims/witnesses.

Known as The Sketch Cop, Mr. Stroud explains his handling of victims/witnesses this way: “They are really nervous. They are really wound tight. I have to develop a rapport and get them to feel comfortable with me. They start talking and before we know it, we have got a face.”

And it’s not only about suspect renderings; police forensic artists also compose hypotheses. Our neighbors to the north, Royal Canadian Mounted Police show us one of their artists at work on an age-progression piece depicting a missing person and what she looks like years later.

(Photo courtesy of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.)

“Age-progression sketch artists take the last known available photograph of a person and age that person in a new drawing to [envision] how they could appear today,” wrote a Royal Canadian Mounted Police spokesperson.

Similarly, the Miami-Dade Police Department’s forensic artist unit goes beyond drawing composites of suspects. Samantha Steinberg also does projections: what people may look like with age-progression techniques:

Reconsidering technology, especially the advent of software allowing artists to generate portraits by touching a pentel to a computer screen (easy on, easily erasable), one may imagine the price tag is rather cost-prohibitive.

Given police agencies endure budget battles annually, affording such a high-end device is difficult, especially for America’s small departments (the majority).

Thus, a skilled police sketch artist, whose drawing pad and professional-grade pencils are about the price of a large pizza (but lasts longer), is an option. The cost of the overlay method we discussed is the middle-ground regarding affordability.

Irrespective of what each police agency can or cannot afford in terms of suspect rendering methods, the key ingredient is not only pencils or overlays or digitized renderings but a skilled police practitioner patiently listening and deliberating until the bad actor appears on surfaces. Then, patrol division cops can sleuth the beats until a prospective match is detected.

One last note: besides police artists coming to the table with organic skills honed before they joined the job, the FBI offers coursework and certifications. As well, the International Association for Identification (IAI) teaches “Standards and Guidelines for Forensic Art and Facial Identification.”

Incidentally, although I maintained a love for pencil portraiture throughout my career, the street beat drew me in, reserving pencil time as an off-duty de-stressor.