Recently in California, an agitated man threatened to shoot a few people before fleeing in a car. Those victims contacted cops and provided a description of the individual and the automobile he was driving. A BOLO (Be On the Lookout) was broadcast over police radio frequencies.

A few police officers observed the suspect driving the reported vehicle and initiated a traffic stop—a felony stop (aka “high-risk vehicle stop”), given victims’ reports of a firearm and the man’s stated intent to use it.

In felony-stop scenarios, the everyday protocols of routine traffic stops are anted up significantly. In certain respects, tension is in the air, but there is no cop walking up to a car window (keep that point in mind as this unfolds). Every cop on the felony stop exercises cover and concealment protocols. In context, one cop takes charge of voice commands. Instead of the routine traffic stop whereby law enforcement officers walk up to the vehicle driver, a felony stop is the polar opposite—every occupant of a car involved in a felony stop is methodically directed to slowly exit and follow verbal directions of the main police speaker. Firepower is prevalently pointed.

This felony stop situation happened to be in a shopping center —in close proximity to a Walgreens— elevating the vulnerabilities which law enforcement must take into account. Tactical deliberation is paramount.

Fullerton PD’s public information officer stated, “The suspect was uncooperative and barricaded himself inside the vehicle.”

Bearing that in mind, our suspect wanted to run the show. He requested cops walk up to his window so he could talk. Not gonna happen. Based on reports of an armed individual threatening to shoot people then fleeing, tea-time is off the table. The propensity for suspect(s) to employ violence exists. As expediently as possible, police attempt to study/learn this individual.

Specifically outlining how to handle barricaded suspects, the International Association of Chiefs of Police published (IACP, May 2020) “Response to Barricaded Individuals,” posing the following to America’s 18,500 or so police agencies: “The primary goal of law enforcement response to barricaded individuals is to save lives and to resolve crisis incidents while attempting to avoid unnecessary risk to officers, suspects/subjects, and innocent bystanders.”

From a safe distance, cops maintained a perimeter, cleared the area of bystander citizens, and strategically went about engendering dialogue to determine the issue(s), de-escalate matters, and safely take the suspect(s) into custody.

Time ticked as the standoff ensued. Talks transpired for over one hour. Within that hour, police rolled a Bearcat to the scene. Bearcats are those supposedly scary armored vehicles Mr. Obama deemed too militaristic and not what citizens want roaming American streets. Technically, they don’t roam around as patrol cars do. Bearcats are generally parked in the police HQ compound, usually nestled away from more actively used vehicles, until absolutely needed (otherwise known as a “callout”). But hey, he had to paint a picture worthy of pander—fictions be damned.

(Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Police Department SWAT team.)

If you’ve ever seen any footage of our military forces coming under attack in certain Middle East nations, then you know what Bearcats look like, why they are used, and how effective they can be in saving lives (in our example, both civilians and cops). So, there is that aspect among the police array of deployable equipment to quell volatile situations. In Florida and other hurricane-prone states, Bearcats are used to pluck people from natural disaster-caused perils such as flooding. My department cohorts referred to our Bearcats as “heavy technology,” primarily employed by our SWAT team.

Operational Containment

In Fullerton, that heavy technology Bearcat’s steel body and reinforced windshield was strategically placed directly in the pathway of the suspect vehicle, purposed to prevent forward momentum. Similarly, a police SUV was parked behind the suspect’s car, preempting (or at least slowing) any attempts to throw it in reverse and mash the accelerator, potentially using his car as a plow and/or means of escape.

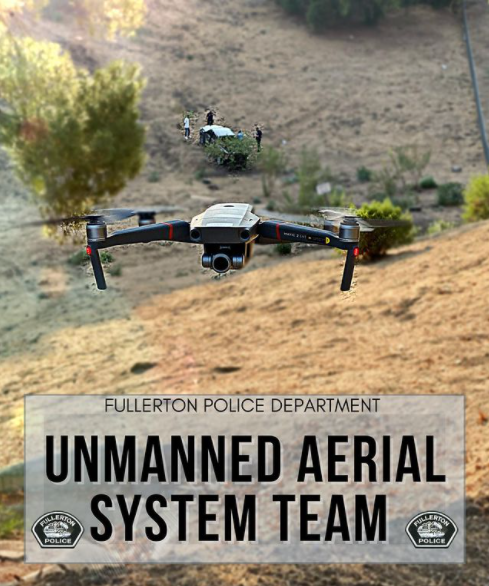

Blocked in, talks were the tall order. Pursuant to IACP guidelines and Fullerton PD’s policy criteria being satisfied, a “small unmanned aircraft system” was employed and operated from a safe distance.

Among its deployable assets, the Fullerton police force has drones operated by a trained and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) certified operator categorized as a “public safety and government user.” Neighboring police entities without a drone unit (affordability is a factor, thus larger departments are usually equipped) typically request a certified police drone operator under a mutual aid covenant.

Fullerton PD’s drone program is fairly new, commencing a modest specialized unit to enhance its capabilities in the public safety mission: “The Fullerton Police Department initiated its development of the UAS Program in 2018 and spent the next two years researching the project before its implementation. While developing the program, the Fullerton Police Department studied the use of the UAS technology in public safety operations around the country, while also researching best practices, policies, and procedures regarding the use of UAS technology in law enforcement.”

Before getting their drone unit off the ground, “five sworn [Fullerton] police officers were trained in the operation of UAS technology and earned required commercial licenses (FAA Part 107) and certifications necessary to operate UAS’ in the performance of their law enforcement duties. The UAS Program has been approved with a Certificate of Authorization from the Federal Aviation Administration for use as a Police Agency.”

Since their maiden voyage with drones, Fullerton PD expanded their UAS Program to eight FAA-certified police operators supervised by a corporal, sergeant, and lieutenant, with ongoing training just like any other police facet.

(Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Police Department.)

Big Birds and Little Birds

Fullerton does not own a helo (when needed for vehicle pursuits and the like, they request mutual aid from nearby police entities which do own helicopters). In the case of our barricaded subject discussed herein, noise reduction is a key element not only to garner communication/information but also maintaining a sense of calm so crucial in the context of talking down a hypersensitive individual triggered by potential mental burdens. Ever been close to an airborne drone? Compared to a helicopter’s excessive din (and wind), drones barely emit a buzz, are cost-effective, and efficient—the difference between burning fuel or a rechargeable battery.

Obviously, both helicopters and drones are deployed in police work, but only one employed for various purposes is extremely lightweight and compact:

In terms of paramount officer safety, we all know helicopters can entail mechanical failures and potentially cost lives after a plummet to the ground; drones alleviate all that. In my police career, I’ve known two police pilots who were lost in helicopter crashes in my area, at a time when drones were not as en vogue as they are now.

Also, in comparison to helicopter capacities, drones have impressive video/still photo resolution, providing excellent details of a suspect and the environment in which they are operating.

Regarding that last part, that is how law enforcement was able to determine that a frightened, battered dog was in the suspect’s car. Incidentally, footage and photos gathered by drones are used as evidence toward successful prosecutions of offenders. Additionally, drone-gathered imagery, particularly video/audio footage, is incorporated into police-academy and in-service scenario-based training, dissecting pros/cons and denoting where improvements can be made.

The drone’s focus capability and easy portability enable police personnel to observe details up-close, without having to endanger human counterparts. Akin to robotics, why imperil a human when you can deploy a replaceable device to do the job?

As a drone aspirant, I chat with UAS operators whose club convenes in a local park overlooking the Gulf of Mexico. The consensus is that the only remaining drawback to flying drones is the short-lived battery capacity (“about 30 minutes before it needs to be landed and batteries switched”). Hopes are high that manufacturers are working on bettering that factor. That likely explains why reports of “found drones” pop up in community forums. On the non-technical side, birds with burning curiosity tops the list of strange encounters with drone aviation, at least among hobbyists flying in coastal environs where birds are always fishing the waters.

Fullerton PD’s post-incident presser included, “After approximately an hour of negotiating with the suspect and utilizing the UAS [Unmanned Aircraft Systems] drone team, we were able to communicate and get him to surrender safely.

From the Fullerton PD blotter: “At 2:50 PM today a 37-year-old male from Santa Ana threatened with a firearm two subjects that were walking on the trail by the courthouse at 1275 N. Berkeley. The suspect left the location.”

According to the Fullerton Observer, “An injured dog was located inside the vehicle. Animal Control arrived on the scene and deemed the dog’s condition to be associated with animal cruelty. The suspect was arrested for felony criminal threats, resisting a peace officer, and animal cruelty.”

(Photo courtesy of the Fullerton Police Department.)

As for the rescued dog, police officers involve animal control officers and ensure veterinary care is implemented immediately. A happy ending to this saga may entail one of the involved cops adopting the beaten dog found inside the suspect’s vehicle. Animal cruelty charges adjudicated via due process ordinarily culminate in court-ordered prohibition against rejoining the victimized animal with the abuser.

With the male suspect arrested without further incident, a dog saved, and drone instrumentation doing most of the labor and evidence collection, officer and public safety was assured.