April marks Autism Awareness Month, bringing about all-things autism, emphasizing the iconic blue solitary puzzle piece idled…symbolizing the desire to fit in to the planetary placement of people with respective uniqueness. I am more than intimately aware of autism: my daughter is intensely autistic with comorbidities, including self-injury and non-verbal nature. My Haille communicates via American Sign Language (ASL) cues.

Early on in my law enforcement career I was tapped by the police chief to join a research team at the University of South Florida think tank named the Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (CARD). Over the course of several visits, varying members of the research team interviewed me with specific intent: How does a cop handle calls having involving someone on the autism spectrum? Biased as I may be, I marveled at the notion for a non-governmental entity to delve into such imperative subject matter, meaning there was not much material specifically for cops to implement for calls involving an autistic person. That was a few decades ago.

Autism is indubitably complex. Given the chronic woes cops confront on the daily, are LEOs adequately aware/trained for situations engendering autism? “Stimming” is a self-soothing thing employed by autistic individuals as a coping mechanism. Waving hands or tapping fingers on countertops is stimming, yet an untrained public safety official may perceive stimming as a prelude to an aggressive act or defiance if asked to stop making such a gesture. Awkward and, frankly, understandable…from a cop’s perspective.

As a police dad who knows well the sensitivities experienced by autists, the general population does not necessarily consider autism and its multifaceted constructs across many layers endured by people in different degrees. Hence why it is identified as “spectrum.”

The research I referred to above culminated in a handy tri-fold brochure of literature geared toward cops to use as a sort of cheat sheet to help identify and delicately mitigate police calls involving anyone with autism. (Some mishaps were made in different parts of the country wherein autistic-related behavior and police personnel attempting to handle aggression or seeming disobedience resulted tragically.)

Law enforcement has come a long way in its awareness and protocols relating to individuals diagnosed with autism. Many of these instances to which I allude were based in non-verbal autistic people who “wander” and require an all-out search-and-rescue posse, often led by cops and volunteers who specialize in this sort of operation.

Commendably, states like Florida legislated autism training for all law enforcement officers within its jurisdictional boundary. Across the country, more and more police departments are broadening their skill-base, either attending autism training or putting together a class and offering it to LEOs. One such grand success has been the Montgomery County Police Department whose autism training includes the best teacher around: a young teen who has autism, one who can boast he has trained over 2,500 Maryland cops on the topic of autism. Enter Jake Edwards, “Montgomery County Chief Autism Ambassador” whose “brain works very, very fast.”

Montgomery County police Officer Laurie Reyes (immediately to Jake’s right) is her department’s “autism/intellectual and development disabilities (IDD), Alzheimer’s, dementia outreach coordinator.” Heckuva title which is succeeded with a huge heart and compassion, and that is exactly why the U.S. attorney general recognized/awarded her and the MCPD’s Autism Outreach Program in September 2018.

The following video portrays Jake and how he is trying “to help people in a neuro way,” all walks of life from the police to the Pope:

That is a microcosm of cops and autism awareness forging official capacities. But, like me and mine, there are grassroots stories of police parents and their respective autistic child/children. My newsfeed is abuzz with matters which pertain to me, such as police culture and autism—personal experience is the magnet.

As such, I came upon a poignant law enforcement-related nugget having to do with a deputy dad and the special relationship he has with his autistic non-verbal daughter, “Drew.”

A short video posted by the Coweta County (Georgia) Sheriff’s Office depicts Deputy Mark Dorsey preparing to embark on his daily duty with the Patrol Division, his daughter providing a send-off kiss prefaced with a bevy of sign language cues. With permission of both the Dorsey family and CCSO, we witness the special bond between a deputy dad and his daughter Drew:

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=682993072498311

Advocating cool cop stories, the National Police Association contacted the Dorsey family and learned how fascinated Drew is with her daddy’s duty flashlight—playing with it, testing it. You never know: a surprise inspection might happen, and Drew has dad’s hardware all up to specs. Drew’s mom and Deputy Dorsey’s wife, Brittany Dorsey shared how Drew helps her dad prepare for duty, ensuring he is fastened securely and festooned with all the tools of the trade. Brittany shared, “Drew loves routine. She likes watching him get ready and helping put his work belt on.”

About that iconic tool on any cop’s duty belt —the flashlight— Brittany described Drew’s thrill from dad’s sort of…magical wand: “Her favorite thing on his [duty] belt is his flashlight. She shines the light all throughout the house for several minutes before she allows him to attach it to his belt.” I remember those days, my daughter tinkering with items I employ on duty (minus firearms, of course). I always cherished this ritual as a piece of Haille with me while on duty. I imagine Deputy Dorsey defines it similarly.

Albeit via silent communications, autistic children usually find their own special way to telegraph what is on their minds. My daughter (especially since I retired from law enforcement) will consistently walk to any marked police cruiser she sees when out in public. It’s her way of claiming recognition for a thing; she spent years observing my marked police cruiser in the driveway, so this logically follows in how non-verbal autists adapt to their environment and adopt certain things in it—essentially, what she grew accustomed to in her world. I once asked a neurologist specializing in autism: Does she know I’m her dad?

That doc’s response was pointed, a bit dour, but understandable and eventually acceptable. He replied, “She knows you belong to her.” It was something…something good enough for me, given the neuro dynamics we know as autism.

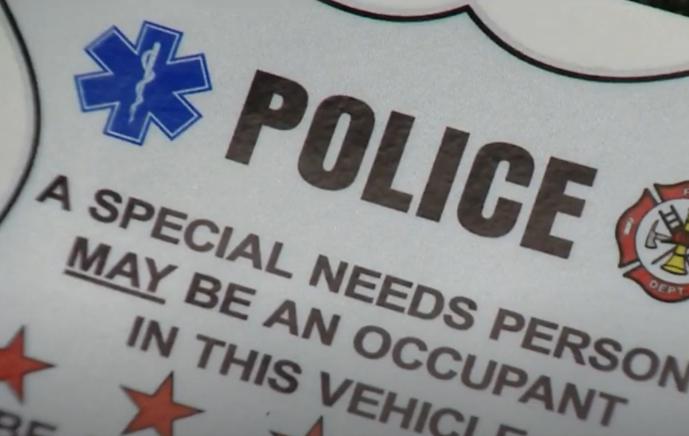

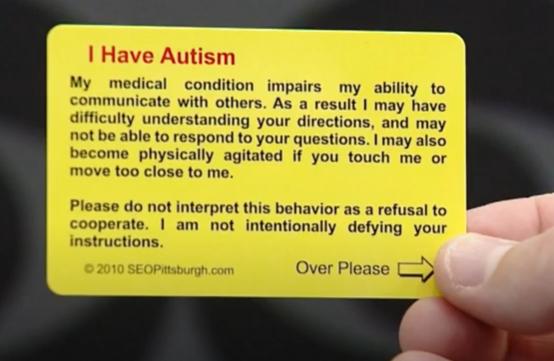

Speaking of belongingness, non-verbal autists are predisposed to challenges by the very virtue of not having the ability to talk. Like those distributed to a blind or otherwise disabled citizen, a small laminated “I Have Autism” card (often referred to as a “wallet card”) explaining someone’s particular disability goes a long way to help a questioning cop to more readily understand the nature of matters at hand.